At the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix, Ayrton Senna, in only his second season in Formula 1 and in what was only his second race with Team Lotus, delivered an absolute masterclass of wet weather racing.

By the time of the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix at Estoril, it was no secret that Ayrton Senna was something special. He had proved it a year earlier in Monaco when, in atrocious conditions, he was first across the line, when Clerk of the Course Jacky Ickx, stopped the race on the grounds of safety. With the final finishing order taken a lap earlier, the victory was awarded to Alain Prost, the first of the Frenchman’s four wins in the Principality. This is not the time nor place to explain why many view the race stoppage as being about as fishy as a “Dorade” left to rot on the Monegasque harbour wall!

In 1984, young Ayrton was at the wheel of a generally uncompetitive Toleman, but at least he was in Formula 1. He was never going to stay there long and by the following year, he had joined Team Lotus. But its founder Colin Chapman had passed away and its glory days were far behind it. However, the 1985 Renault powered Lotus 97T proved to be a step in the right direction and in the first race of the season in Brazil, both Senna and team-mate Elio de Angelis qualified on the second row. De Angelis finished third, but Senna retired with an electrical problem. Next stop Estoril for the Portuguese GP…

Ayrton Senna at the Portuguese GP, Estoril 1985. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

Ayrton Senna at the Portuguese GP, Estoril 1985. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

The Brazilian had been quick in practice and, come qualifying time, no one could touch him. He hustled the distinctive black and gold Lotus around Estoril to post a pole position time almost half a second quicker than Alain Prost in the McLaren and a second quicker than his team-mate De Angelis. Remember these were the days of “qualifying special” engines that only had to stay in one piece for a few laps before de-tuned versions were then swapped in for the race. These turbocharged beasts could push out upwards of 1000 horsepower. So the problem was in making the super sticky Goodyear qualifying tyres last a whole lap. This was where Ayrton shone, through a sixth sense through the seat of his pants and just sheer natural ability, dancing the car on the limits of adhesion, with that strange throttle-stabbing technique which began in his karting days and that he would gradually develop still further.

Ayrton Senna (centre) on the podium after winning the Portugese GP. Estoril 1985. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

Ayrton Senna (centre) on the podium after winning the Portugese GP. Estoril 1985. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

Come race day and the heavens opened, making car performance very much a secondary consideration with driver skill becoming the key factory. Starting from the first of his 61 pole positions, Senna led off the line and proceeded to give a virtuoso performance. In the space of just 10 laps, he already had a 13 second lead over his De Angelis in second place, with the masterclass continuing as the gap grew to an unbelievable 30 seconds, ten laps later. There were a couple of scary moments, when the Lotus visited the grass, but apart from that it was a masterclass. The race ended at the two hour time limit, as the rain meant it did not go the full distance in terms of the number of laps. Senna had led from start to finish in a race with no Safety Cars, no pit stops, just two hours of high tension. For the Lotus crew who had only won once in the past six years and whose founder Colin Chapman had passed away three years earlier, it was a very special day. Talking about the race a few years later, Ayrton himself also regarded it as a high water mark.

Ayrton Senna after winning the Portuguese GP in Estoril, 1985. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

Ayrton Senna after winning the Portuguese GP in Estoril, 1985. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

“It was a hard tactical race, corner by corner, lap by lap because conditions were changing all the time,” he recalled. “The car was sliding everywhere. It was very hard to keep the car under control. You often saw cars sliding about all over the place purely through lack of grip and too much power. Even if I had a good comfortable lead it was difficult to keep the concentration, to keep the car under control right to the end. Once I nearly spun in front of the pits, like Prost, and I was lucky to stay on the road."

Aryton Senna

F1 pundits tend to rate Senna’s performance in the wet at the 1993 British GP – the only time the race was held at Donington Park – as his greatest drive, but the man himself disagreed. “I had traction control! Ok, I didn’t make any real mistakes, but the car was so much easier to drive,” he said.” It was a good win, sure, but, compared with Estoril ‘85, it was nothing, really.”

Not surprising, given the youngster had won the race from pole, set the fastest race lap and lapped the entire field apart from Ferrari’s Michele Alboreto, in what was only Senna’s second race for the team.

Ayrton Senna takes the lead during the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix in Estoril. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

Ayrton Senna takes the lead during the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix in Estoril. Image courtesy Motorsport Images.

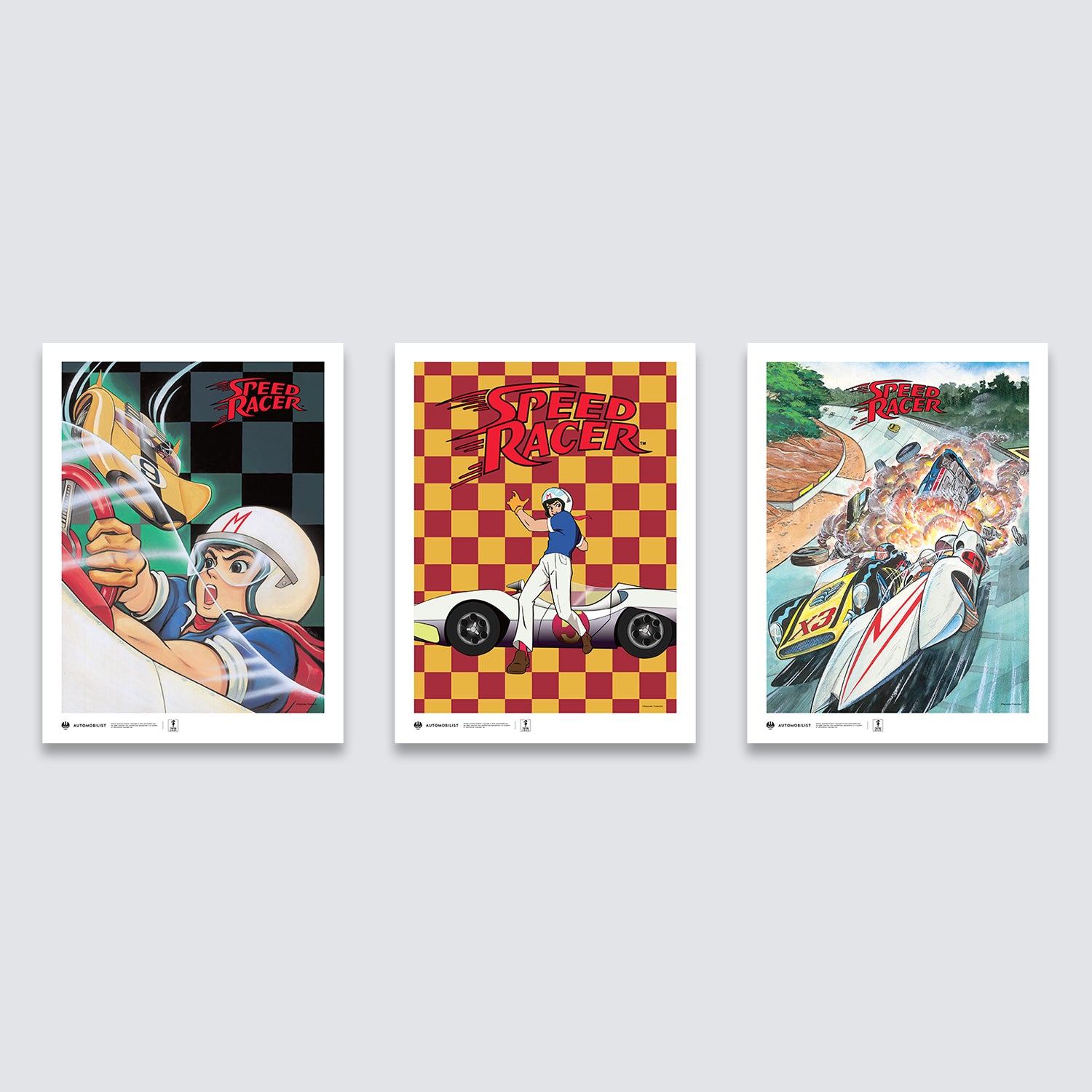

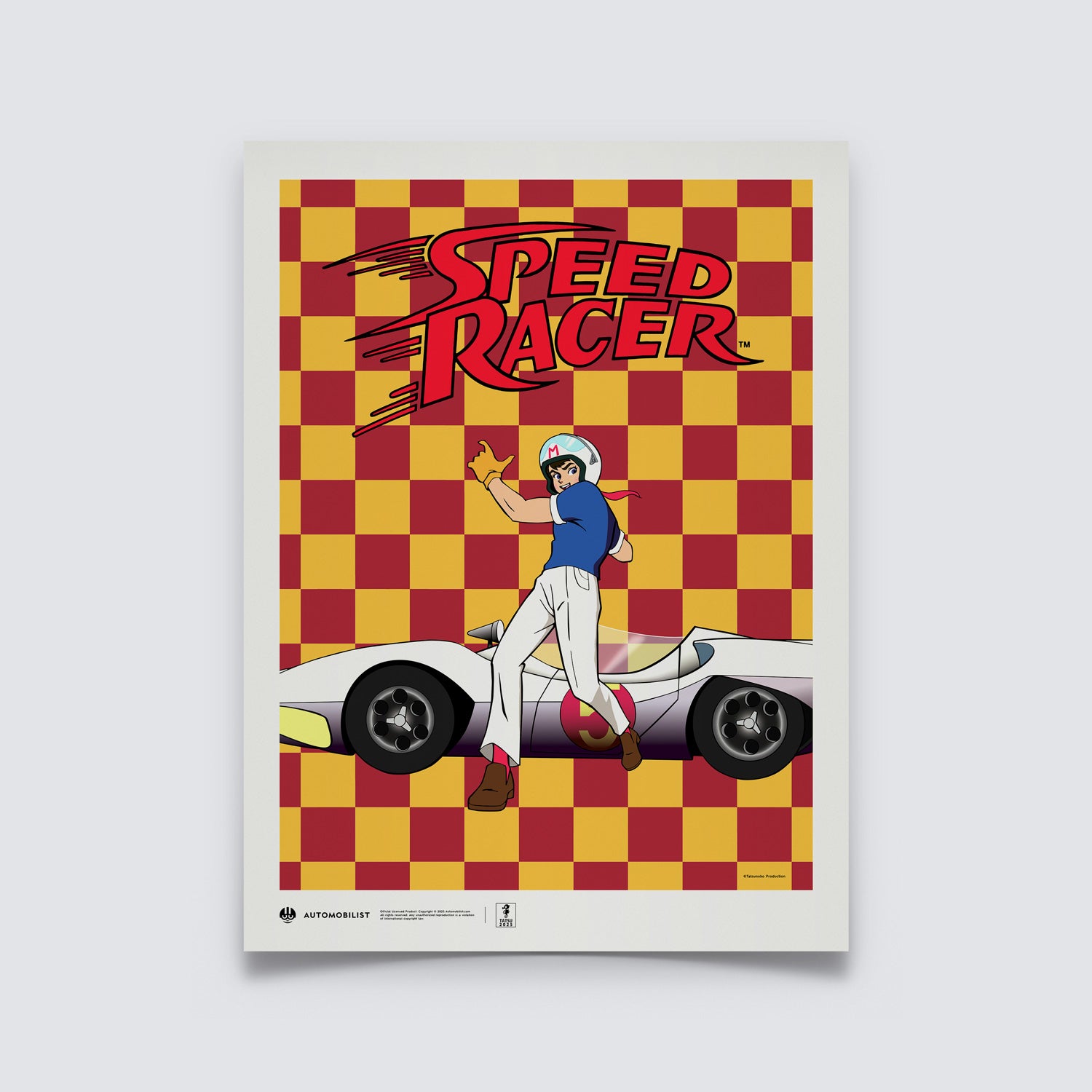

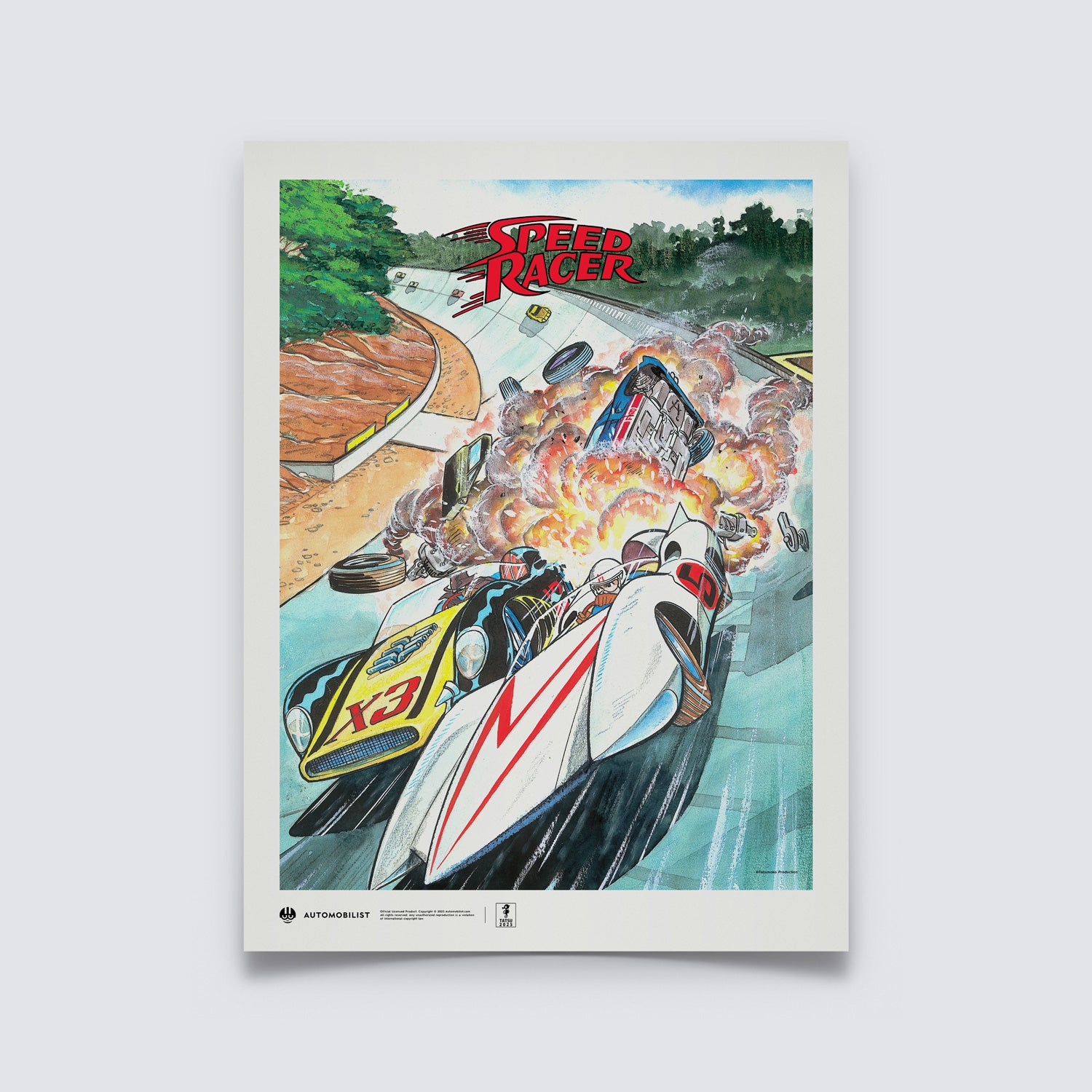

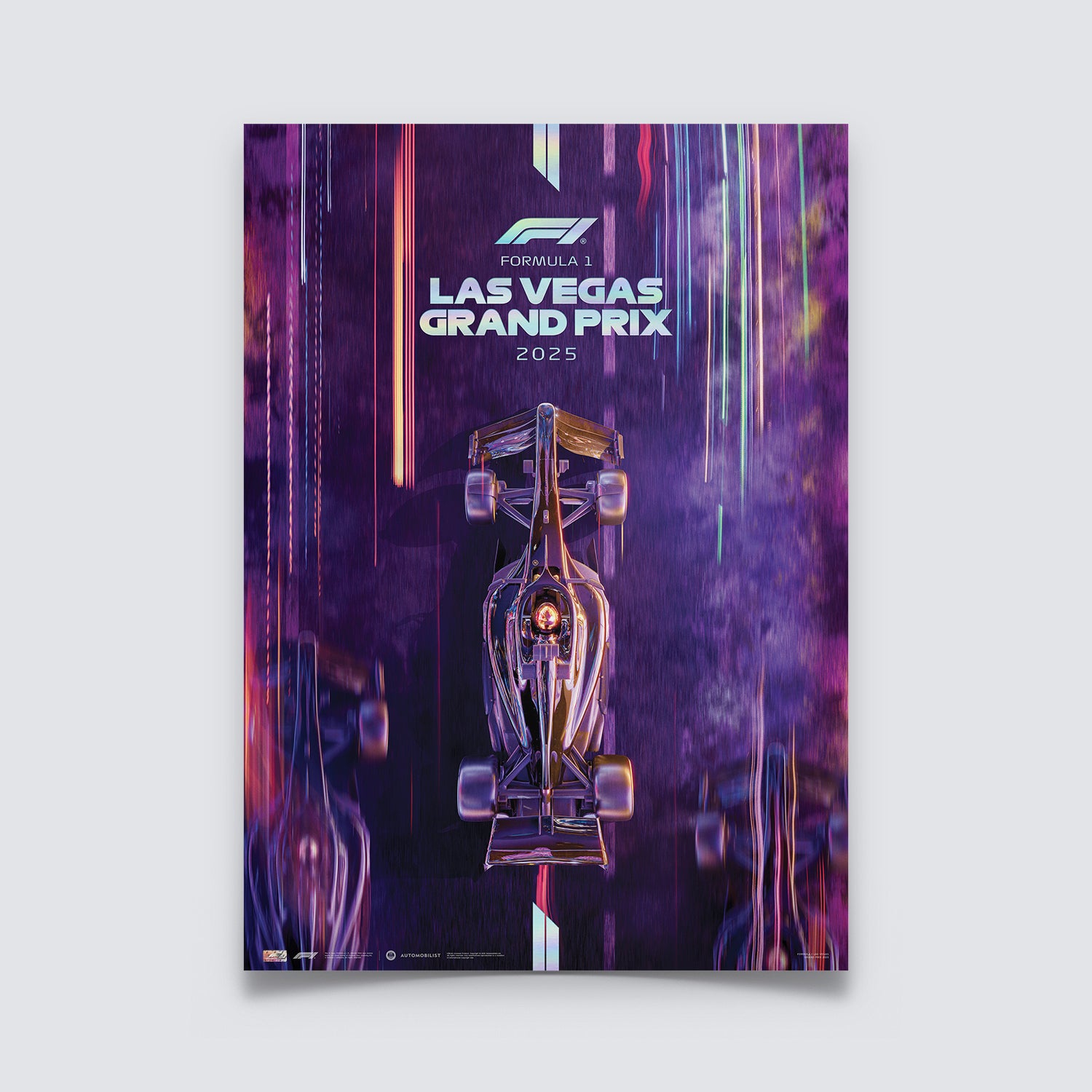

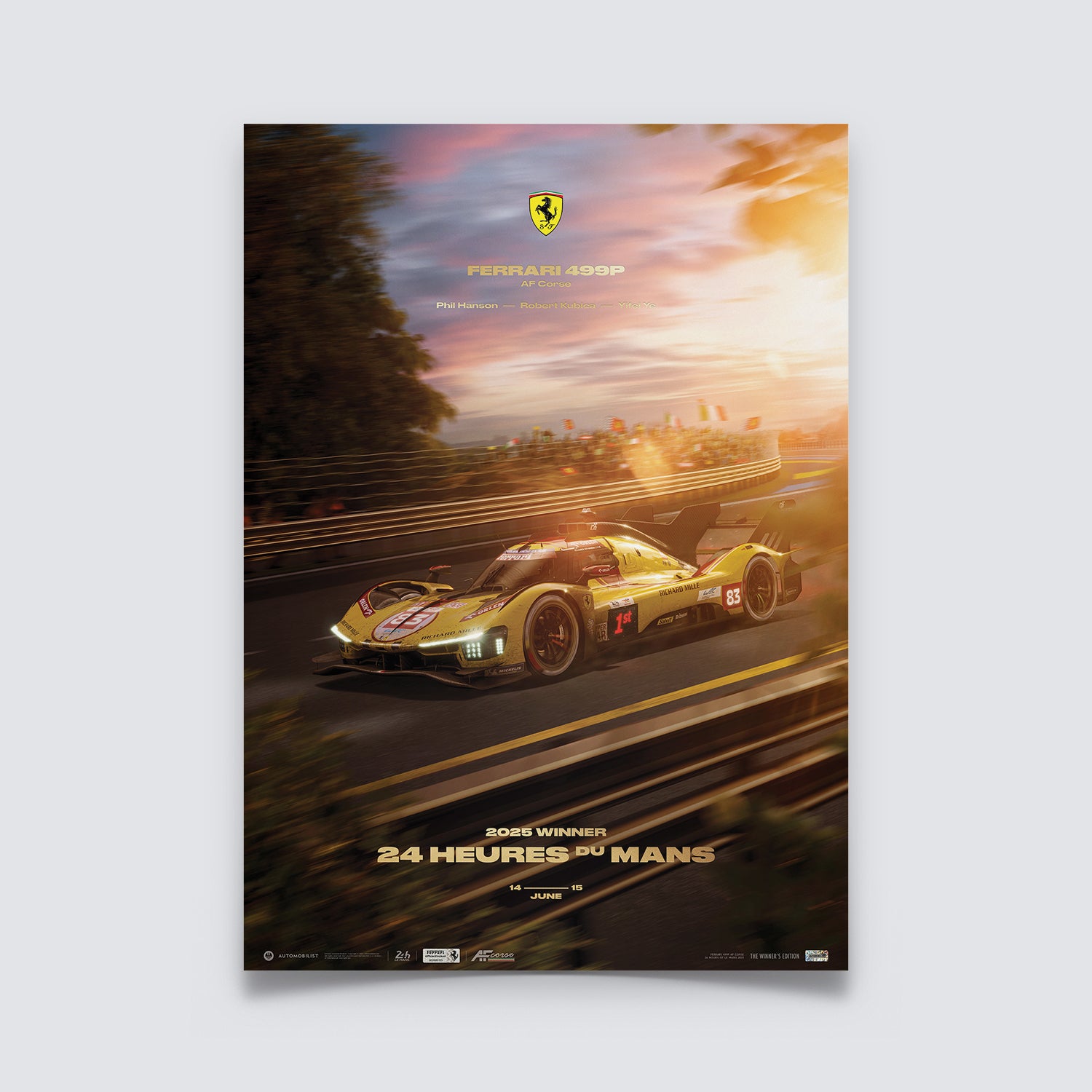

Senna’s brilliant win at Estoril in the beautiful black Lotus was an obvious topic for one of Automobilist’s Fine Art images. Let’s take a look at the work that goes into one of these masterpieces.

The first point to make is that it’s a long process, more so for the Fine Art pieces as they feature more detail. A team of people can work on several projects at once, so the total timeframe can be up to three months. Although photos of that historic day provide valuable information, they cannot be the sole source of reference, because artistic priorities mean some posters feature angles that would be impossible to capture, such as car coming straight towards you down the track. Furthermore, in this instance, we are talking about a black car racing in the rain on a dark day, so there’s a need to augment the reality to provide detail that would otherwise be lost. As an example, the rear wing of the Lotus at Estoril featured a “Gurney” flap and a wire support simply not visible in images from the time. Instead, this information was provided by Classic Team Lotus, who worked with Automobilist through every step of the process.

The starting point was the wheels, a known dimension, inputted into the 3D computer design along with other known quantities, such as the car’s wheelbase. When using a 3D process for a 2D artwork, all the effort is concentrated on those parts visible once the best angle has been chosen. In other words, the underside and rear elements of the car do not exist at all in a head-on shot. Other details are deliberately omitted, given that we are talking about a black car on black tarmac in the rain.

Accuracy is everything, so that even carbon fibre elements that are visible have to look like the carbon used back when this event took place and it’s different to the current material. The minutiae of the technical detail involved in the preparation of the poster in terms of delivering the most accurate rendering of the car itself is combined with the wonderful artistic work that goes into providing the dramatic background to the car – the lighting, capturing the ominous dark skies and wet track of that historic day in Portugal. Only when the artistic and the technical come together do we have something worthy of the name Fine Art. Ever the perfectionist, we like to think Ayrton Senna would have approved.