24h Le Mans Centenary: 1963-1972 | Written by Richard Kelley

Having tasted their first Le Mans’ winners Champagne in 1971, Porsche pulled out all of the stops for a repeat victory the following year. Of the 49 cars that burst off the line at the drop of the flag in 1972, an astonishing 33 were Porsches.

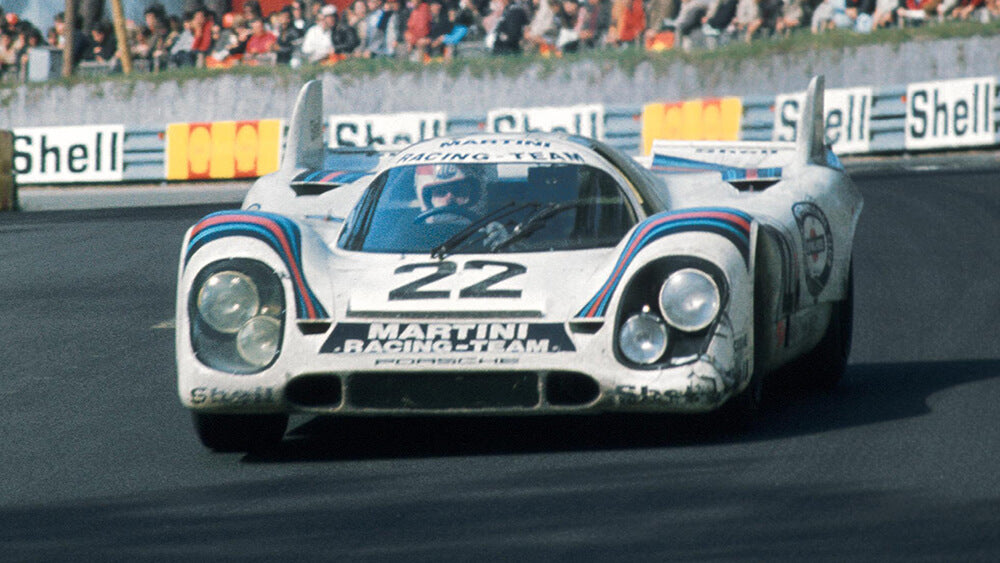

When the dust settled 24 hours later, Helmut Marko (third in 1970) and Gijs van Lennep soaked their Martini-liveried 917-053 Kurzheck with the bubbly celebrating their dominant victory. Having completed 397 laps, they set a speed record that would last for 39 years.

Even more remarkable was that Porsche had now thoroughly tamed a racecar that, just two years earlier, was deemed almost un-driveable at high speed by even the finest of drivers.

What changed? Aero tweaks, weight reductions, and increased engine power to 630 hp across the teams.

Podium atmosphere, with Dr. Helmut Marko and Gijs van Lennep, 1st position, among those celebrating victory at the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

Podium atmosphere, with Dr. Helmut Marko and Gijs van Lennep, 1st position, among those celebrating victory at the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

“I was never afraid of any understeer or oversteer because it was so nicely balanced,” recalled van Lennep, “and you could drive it on the throttle fantastically because it had a 100% locking limited-slip differential.”

However, Porsche engineers had one more solitary improvement remaining. They bestowed chassis 917-053 with an ultra-lightweight magnesium frame.

Porsche racing engineer Norbert Singer remarked that the weight savings was significant. At that time, 917s routinely came in 44 to 66 lbs heavier than the 1764-lb minimum weight required in the 5.0-litre Sports class in which they competed, primarily because of the heavy flat-12 engine out back.

So Porsche experimented with magnesium chassis tubes instead of the standard aluminium.

A view inside the Porsche garage with the winning 917 KH on the left, and the retiring 917 LH and 'Pink Pig' 917/20 at centre and right. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

A view inside the Porsche garage with the winning 917 KH on the left, and the retiring 917 LH and 'Pink Pig' 917/20 at centre and right. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

“The first chassis they made broke after a couple of hours of testing at Weissach,” recalled van Lennep. “That second chassis they drove, I think, for 10 or 12 hours. It was difficult welding at the joints, so they had put a sort of sleeve over it and welded on that. The third magnesium frame was ours and it saved about 40kg, making us the lightest car.”

Unfortunately, magnesium has one flaw. It is wildly unsafe—the metal ignites easily and burns super hot, often over 5000 degrees F. It's also tough to extinguish: dousing a magnesium flame with nitrogen or carbon dioxide does nothing to stop the fire. Even pouring water on burning magnesium creates new flammable compounds that intensify the fire.

Thus, Marko and van Lennep faced the challenge of concentrating for 24 hours in a racecar that produced intense heat that could ignite the chassis (or worse).

Within a few laps, their cockpit, surrounded as it was with an oil tank, magnesium chassis tubes, an oil radiator the size of a twin bed, and that whirring, howling 12-cylinder engine behind them, became not only warm but intensely hot.

Mis-shifts would be catastrophic. The engines were safe to 8,200 RPM; they exploded at 8,500. Thus, limiting the red line to 7,500 was critical.

Gijs van Lennep at the wheel of the Porsche 917 KH during the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

Gijs van Lennep at the wheel of the Porsche 917 KH during the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

The Wyer Gulf team's two 917 LHs of Pedro Rodríguez/Jackie Oliver and Derek Bell/Jo Siffert dominated the early hours until their second car stopped with wheel bearing problems.

Before the race, F1-ace Rodríguez had publicly stated he would employ patience. After all, this was “an endurance test, not a Grand Prix”. But when the Tricolour dropped, the young Mexican was consumed by the “red mist” and drove flat-out. He dropped out with a burst oil pipe in the dead of night.

Ferrari inherited the lead until Nino Vaccarella / José Juncadella lost their clutch.

Meanwhile, the 917-053 showed mechanical sympathy and clockwork consistency. Marko and van Lennep babied the cooling fan: if it broke all its locating bolts, it would fly off, possibly starting an engine fire that threatened their vulnerable frame.

Such a failure had already sidelined Martini’s long tail, which Elford shared with Gérard Larrousse.

“So at every pit stop, a mechanic changed one bolt,” recalled van Lennep. “That way, we didn’t lose any time, and after four pit stops, we had all new bolts.”

Dr. Helmut Marko at the wheel of the Porsche 917 KH during the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

Dr. Helmut Marko at the wheel of the Porsche 917 KH during the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

Frantic to stop the Martini juggernaut, other teams pushed themselves into several high-profile retirements, allowing the Helmut Marko/Gijs van Lennep 917-053 car to seize the lead in the 13th hour and disappear into the distance, or so they thought. With five hours to go, their brake discs began cracking.

“That was the first time we had holes [drilled] in them and they were cracking around the outside,” stated van Lennep. “If we stopped to change them we couldn’t win. So we decided not to brake anymore – or to do less of it at least.”

At the flag, Porsche’s 917 would win Le Mans again, with second place falling to Richard Attwood and Herbert Müller at the wheel of the only other surviving 917 (short version) fielded by the Gulf team.

Dr. Helmut Marko / Gijs van Lennep, Porsche 917 KH, 1st position, returns to the pits after the race to the cheers of the team and crowd at the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

Dr. Helmut Marko / Gijs van Lennep, Porsche 917 KH, 1st position, returns to the pits after the race to the cheers of the team and crowd at the 1971 24h Le Mans. Image Courtesy: Motorsport Images.

Following its triumph on its maiden outing at La Sarthe, Martini's 917-053 was retired by Porsche. It has never been fired up again, simply for fear of what might happen with its ageing and fragile magnesium frame.

It is, therefore, a one-hit wonder, indeed “won and done.”

Follow the link below to read more stories from the 100 years of 24h Le Mans and discover our celebratory poster collection in cooperation with the Automobile Club de l'Ouest.