Throughout the 90s, the impact of technology on people’s daily lives was increasing at a frantic pace, with such developments as the arrival of cable TV, the internet which we charmingly referred to as the world wide web and the arrival of small mobile phones- if you were lucky a NOKIA with the addition of the Snake game for added kudos.

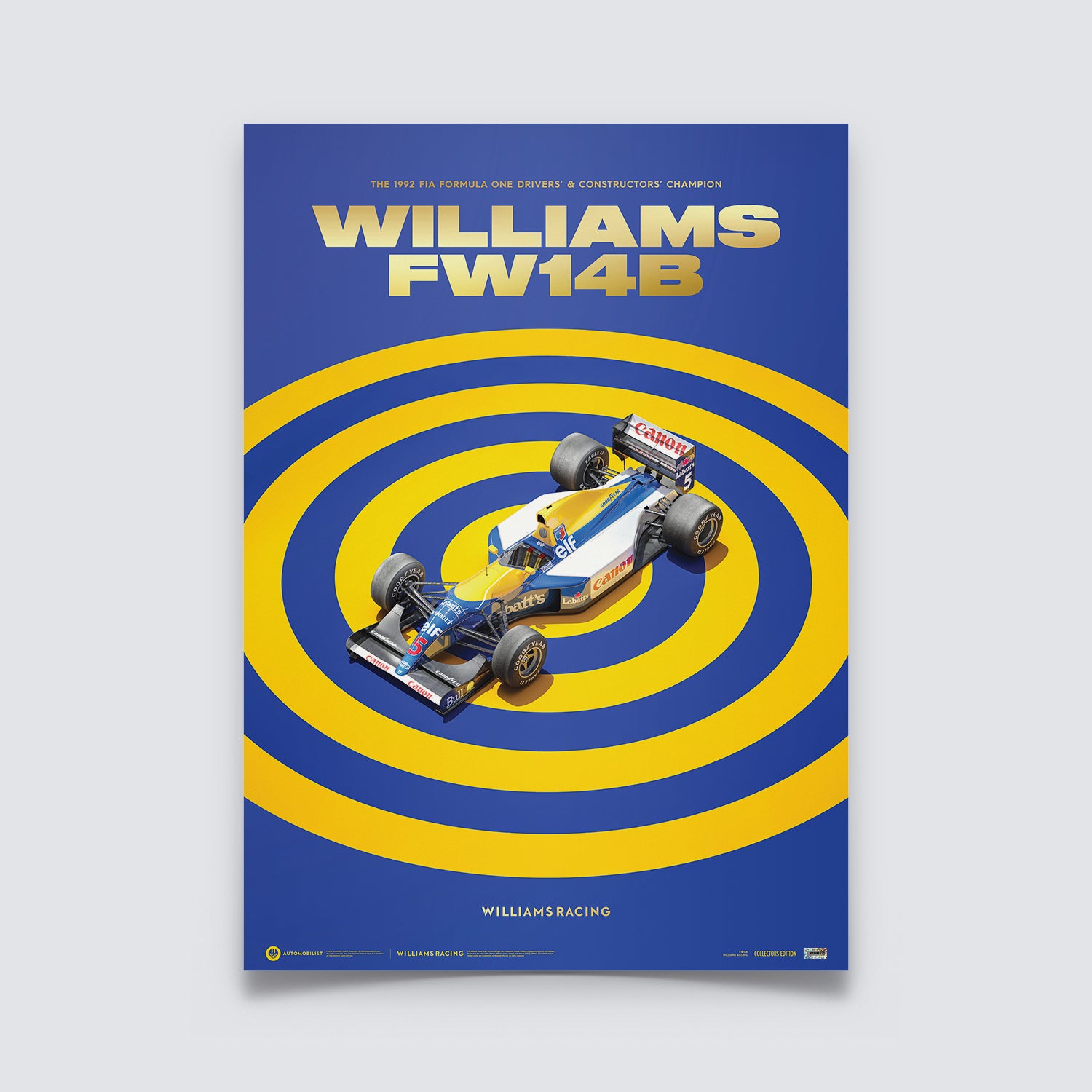

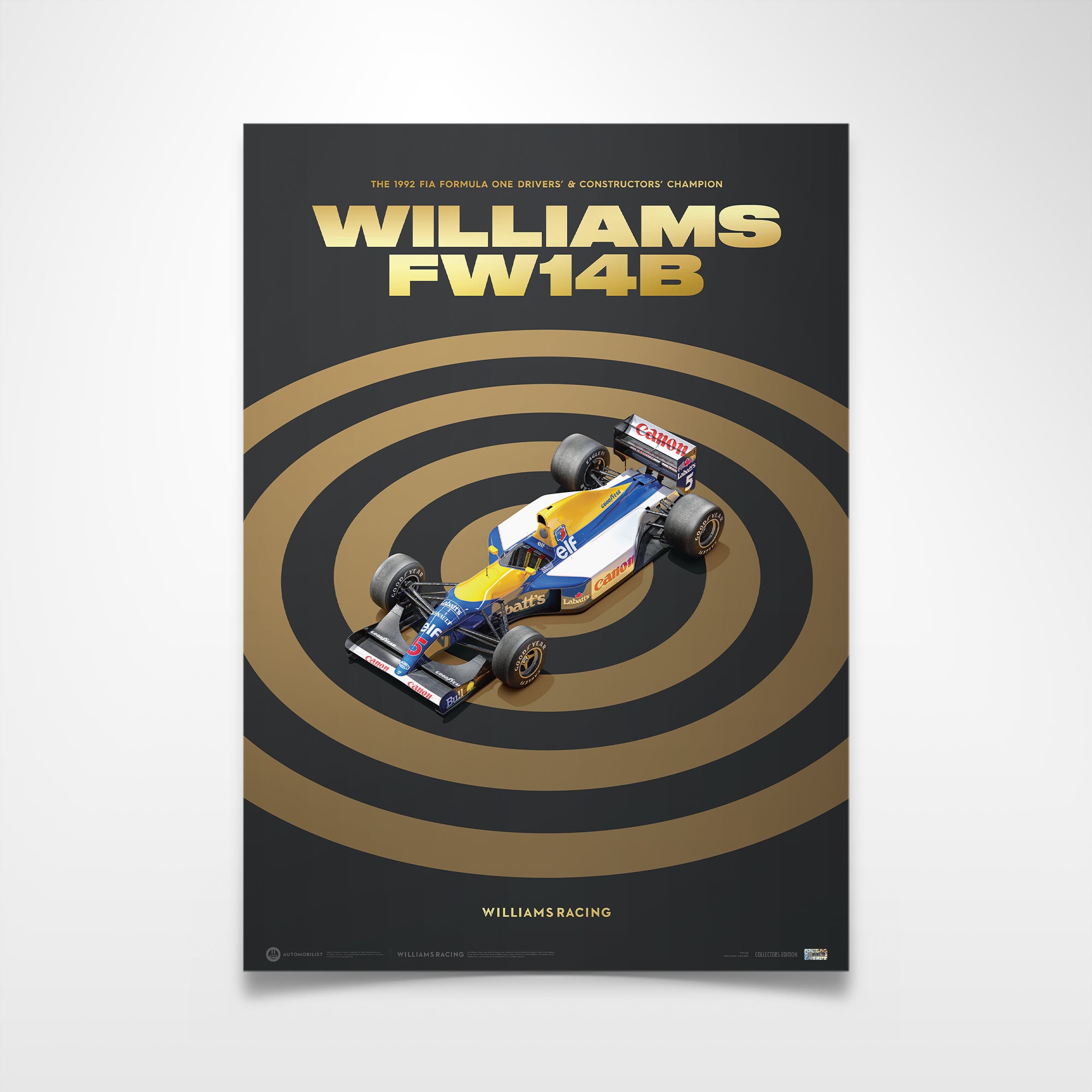

Motor sport has always been an early adopter of new tech and the FW14B which Williams raced in 1992 was by far the most complex Formula 1 car ever seen at the time. It was the first car to really challenge the concept that only the driver in the cockpit should have full control. The car was an evolution of the previous season’s FW14 and it boasted an impressive collection of bells and whistles including a semi-automatic gearbox, a sophisticated blown diffuser to generate downforce, traction control, data logging and, most important of all, electronically and hydraulically controlled active suspension.

Originally developed as a mechanical system for road cars by AP Racing, Williams took their ‘active’ concept and developed an electronic/hydraulic control system. Its primary purpose was to achieve a constant ride height front and rear, irrespective of the vagaries of the race track surface and camber or variations in fuel load, in high and low speed corners. It achieved this through hydraulic actuators, one at each corner of the car, but on top of that sensors in the cockpit measured longitudinal and lateral acceleration and the car would automatically react to these inputs. It could also dial out understeer or oversteer according to the driver’s preference. Back in the Nineties, this was truly the stuff of science fiction.

F1 had seen active systems before, but nothing this clever or effective. The whole package, including a brilliant naturally aspirated engine from Renault, was good enough to end four year’s of McLaren-Honda dominance in the sport. The French V10 was probably on a par power-wise with the Honda, but it offered a stronger combination of power, weight and fuel consumption and was better installed in the chassis, as well as being supremely reliable, and equipped with Traction Control.

The architects of this revolution were a trio of some of the best known names in race car engineering: Williams technical director Patrick Head, chief designer Adrian Newey and electronics wizard Paddy Lowe.

Clever as it was, the FW14B still needed someone capable of driving it. Step forward Nigel Mansell, the team’s undisputed Number 1, with Italy’s Riccardo Patrese destined to ride shotgun for the Englishman. It’s fair to say that Williams has always been the most English of all the English teams in F1 and Mansell always wore his patriotism on his sleeve, or more accurately on his helmet. As the wins began to pour in, with “Our Nige” as he was known, victorious in the first five races of the season, Mansell Mania really took off, mainly in Britain of course. It reached its apogee at that year’s British Grand Prix at Silverstone, when he won by over half a minute and prompted a huge but good natured track invasion, which meant Mansell could not even drive back to the pits on his slowing down lap, abandoning his trusty FW14B out on the track.

All the high-tech toys on the car did not mean it was easy to drive. Quite the contrary in fact, as it would momentarily lose grip at the rear when the driver turned into a high speed turn. Immense bravery or a well developed lack of imagination were clearly required to get the most out of it and Mansell had one or other of those qualities, more likely the former, in abundance. “With any new technology, you're sceptical because it has the potential to kill you,” he told “Top Gear” magazine many years later. “Ultimately, I never trusted it in totality. Basically the car was trying to kill you and throw you off the circuit at every single corner, but it was up to me to stop that happening. Being strong, I had faith that when it kicked out in a high-speed corner I had the skill and the strength to hang onto the car. If it really lost grip, I would drive straight over the kerb, hoping after I went airborne I’d land OK.

The FW14B juggernauted its way to the Drivers’ and Constructors’ World Championship titles, taking 10 wins from 16 races, (nine for Mansell, a single victory in Japan for Patrese) including 6 one-two finishes, 15 pole positions and 11 fastest race laps. Mansell clinched the Drivers’ crown in Hungary, with five races still to go. The following year, Williams won the World Championship again, this time with Alain Prost. Nigel Mansell left the team, despite winning the 1992 title, crossed the Atlantic and duly won the 1993 CART championship at his first attempt, including finishing third in the Indianapolis 500 Mile race. As for active suspension, a system first tried by Team Lotus in the 80s, it was banned as from the start of the 1994 season.

Images courtesy Wilhelm Wolfgang Fotografie / Hoch Zwei