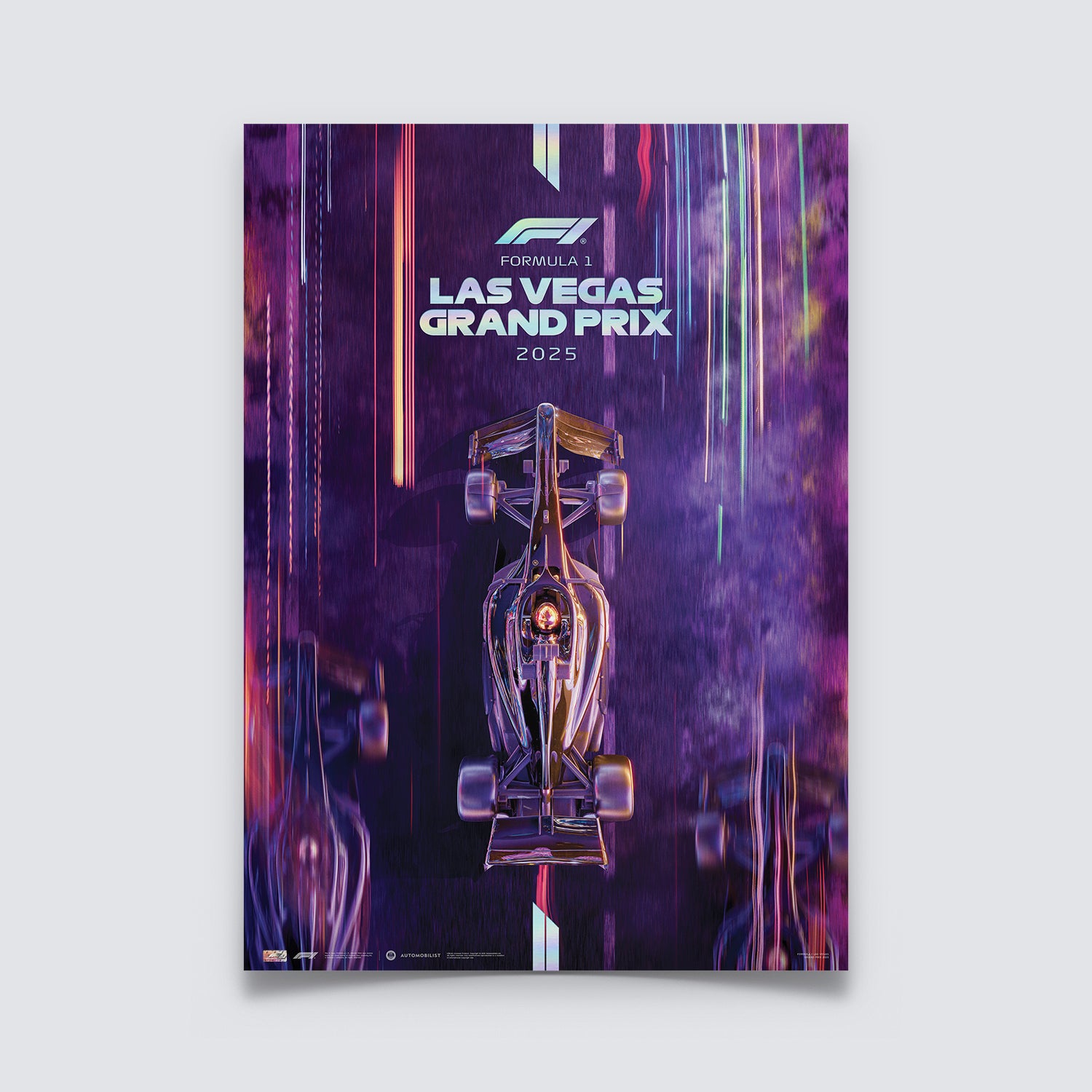

The reason why the Mercedes Grand Prix cars came to be known as the Silver Arrows or Silberpfeil in German is an oft told tale. At the 1934 Eifel race at the Nurburgring the W25 cars entered by Mercedes-Benz were one kilo over the 750 kilos maximum weight limit. Team manager Alfred Neubauer issued instructions for the white paint to be removed, revealing a highly polished aluminium finish and reducing the cars’ weight.

This is the one thing that Neubauer is most famous for, which is a shame given that the German practically wrote the job description for Formula 1 team managers, coming up with a host of innovations that are taken for granted and still in use today. Born in a town near Ostrava in what is now the Czech Republic, Neubauer was fascinated with cars from an early age, joining Austro-Daimler prior to the first World War and becoming head of its test department once the conflict was over. In 1926 he was appointed Mercedes Benz race manager, a post he occupied until 1955.

In his first year in the role, he was amazed that Rudolf Caracciola was unaware he had won the 1926 German GP at Avus, because of the atrocious weather conditions and set about inventing the pit board signals we now take for granted. “I settled down to work out a sort of code system with numbers and letters painted on small boards and a series of coloured flags,” wrote Neubauer in his autobiography. “Then I explained my new system to the drivers, who now had only to glance at the pits as they raced past to pick up invaluable information.” He reckoned that a driver in a race car was “the world’s loneliest human being.”

Neubauer had raced himself, even finishing 16th in the Targa Florio, but in the words of his wife Hansi, he drove “like a night-watchman,” wisely deciding to switch his talents to management. He would become a key figure in Mercedes-Benz success spanning a period of three decades. Alfred would no doubt have approved of the modern F1 pit crew, physically fit and highly drilled, capable of changing tyres in 2 seconds, sometimes less. In his day, things moved at a slightly slower pace, without airguns to speed up tyre changes or high pressure refuelling. But he insisted on getting his mechanics to practice over and over again all the tasks they might face.

Neubauer was also a meticulous note-taker, writing everything that happened in a small black notebook and he would share his wisdom and knowledge with his team. Although a congenial fellow away from the race track, his drivers and indeed anyone in the pit lane, knew better than to cross “Don Alfredo” as he was known. Meticulous preparation was his watchword: for example, before the Mercedes team set off to take part in the 1952 Carrera PanAmericana in Mexico, each member was given a little booklet packed with information about the country, from the food to potential illnesses and what weather could be expected en route. At the track, he stood out not just because of his size but also by the fact he was festooned with stopwatches, usually clutching a red and a black flag to give his drivers various pre-arranged signals. The idiosyncratic team boss also indulged in the flamboyant practice of throwing his hat under the winning car, a move that must have thrilled his supplier of Trilbys!

In the early Thirties, after Mercedes had scrapped its race programme following the Great Depression of 1929, a new car company called Auto Union, asked Neubauer to manage its race team, but Mercedes managing director Wilhelm Kissel persuaded him to stay, promising the company would soon be racing again. Jump to 1950, Neubauer was once more asked to front up a race team and the Mercedes W196 became the dominant force with Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss the undoubted stars behind the wheel. “He was the most sympathetic, but hard-faced man,” Moss recounted many years later. “By that I mean that he was very strict, but he had a wonderful sense of humour. I think he really loved his drivers and took great care of them.”

In fact he would often take all his team out to dinner when he would be the life and soul of the evening, telling tall tales and keeping everyone amused. Actually, there are some who think the whole paint scraping episode to produce the Silver Arrows is a Neubauer tall tale and that the cars were not even painted white.

Truth or tall tale, it matters not: the Silver Arrows legend has served Mercedes very well since the company’s return to the sport as a constructor in 2010.

Images courtesy Diamler / Automobilist