On 16 June in 1903, Henry Ford and eleven investors established the Ford Motor Company, with a capital of just $28,000. Other manufacturers might produce the most expensive, the fastest, the most exclusive cars on the planet, but FoMoCo as it’s known can rightly claim to have brought the motor car to the masses. The model T Ford was first produced in 1908 and over 15 million were sold.

In 1913, Ford invented the moving assembly line for car production, which saw the Model T come off the line at the then unheard of rate of one every 15 minutes. Henry Ford also believed in looking after his workforce, offering a wage of $5 per day in 1914, when the average was half that. In its time, Ford has competed and won in just about every form of motor sport, from Formula 1 to Indy to rallying and Le Mans of course, where it enjoyed so much success with the beautiful GT40.

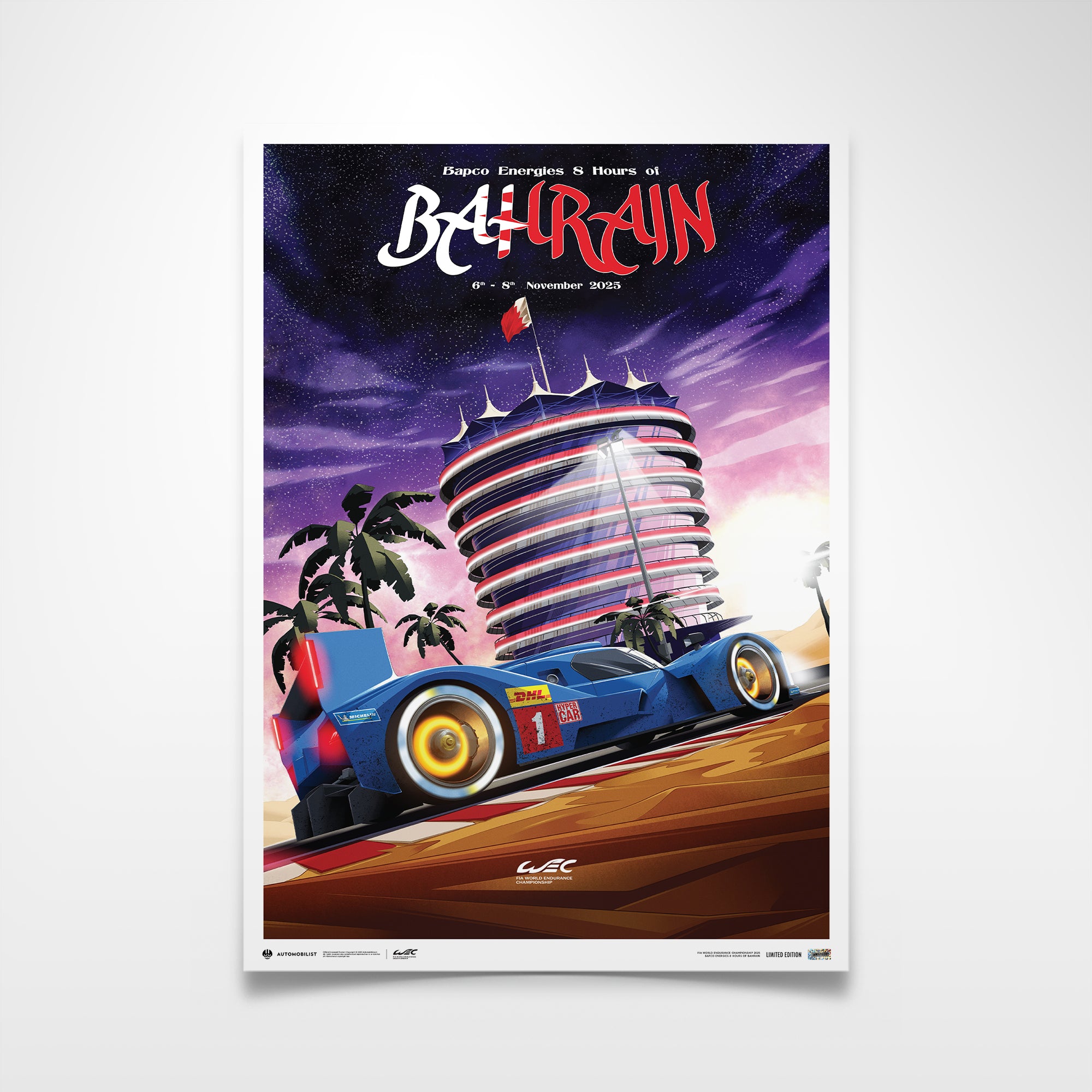

Predominantly from the mid-60s to the early 70s, the World Sports Car Championship, what we know today as WEC (World Endurance Championship) was right up there with Grand Prix racing in terms of the quality of drivers it attracted and the attention it generated among race fans. With grids made up of outlandish looking prototype machines with huge 7 litre engines, mixed in with cars that bore a passing resemblance to sports cars you could buy in the showroom, the maxim “win on Sunday, sell on Monday” influenced several car companies to pour millions into competing in endurance racing.

Henry Ford II wanted a slice of that publicity pie for the Ford Motor Company. He would get there in the end, but the path to glory was far from straightforward. In fact the man most responsible for Ford winning four consecutive Le Mans 24 Hours from 1966 to ’69 was…Enzo Ferrari! The enigmatic Italian had been on the verge of selling his company to the Blue Oval, but the Commendatore backed out of the sale when he was told the deal meant the Prancing Horse team could not race at Indianapolis nor could he run his own race team.

Ford therefore switched its attention to British race car manufacturers, with Lola initially building the car and with Aston Martin’s former race boss John Wyer in charge. Despite the pre-eminence of British firms in the racing world, the project was something of a failure. It wasn't until the whole thing was handed over to the flamboyant Stetson-wearing American racer Carroll Shelby that the GT40, so called because it measured 40 inches in height at the top of the windscreen, set out on the path to legendary status.

Shelby employed English racer-engineer Ken Miles to help develop the car and after two tough learning years in 1964 and ’65, the beautiful car really got into its stride the following year. The Mark II GT40 took a clean sweep of the podium places at the Daytona 24 Hours and Sebring 12 Hours and Ford arrived at Le Mans mob handed with no fewer than eight GT40s on parade. The American cars, with the factory effort entered as Shelby American were up against all the great European manufacturers, first and foremost Ferrari of course, but also Porsche, Alpine, Matra, Alfa Romeo and fellow Americans Chaparral.

We’re not going to give you a blow by blow account of the 24-hour race, but it’s enough to know that in the closing stages, Ford were in the top three places, with the GT40 Mk IIs, crewed by Ken Miles/Denny Hulme, Bruce McLaren/Chris Amon and Ronnie Bucknum/Dick Hutcherson, the latter entered by Holman and Moody. Ford senior management did not want their drivers racing each other and risking anything so they came up with the idea of having the three cars finish in formation. However, the best laid plans do not always come off and certainly, the race organisers, who were informed of Ford’s plan were dead set against it.

Ken Miles, responsible for so much of the car’s development was leading at the final pit stop when he was given the instruction to slow and let the McLaren/Amon car catch up. The two cars duly crossed the line shoulder to shoulder, but it was at this point that the organisers, the Automobile Club de L’Ouest (ACO) pointed out to a rule that this was a 24 hour race in which the winner was the car that had covered the greatest distance in that time. Therefore the McLaren/Amon car, by virtue of being further back for the “Le Mans” start, which involved the cars all lined up down one side of the grid with the drivers sprinting across the track to jump in and drive off, had actually covered about 20 metres more than the Miles/Hulme car and the all-New Zealand crew were thus declared the winners by a distance of about 8 metres.

This unusual end to a truly significant motor sport moment, is beautifully captured in our Fords and the Furious poster, an artwork recreating the staged “photo finish”. The development of this print began in the archives, with our researchers poring over photographs, videos, and technical documentation to build the GT40s in 3D.

After a concept conversation to choose angles, we then developed digital “molds” of the cars with design software, producing models akin to computerised clay. With these as our starting blocks, we then began to texture the race cars – placing graphics, stickers, colour patterns, and oil smudges on the chassis. Additional elements were brought in to create this Fords and the Furious artwork. For instance, to achieve the perfect road glare following a weekend of rain at Len Mans, we did a photoshoot in a water-soaked area with actors to pose as fans and drivers. These photos were then used to help us design a print that captured the race’s final, confused moments with historical precision. Several weeks and 1000 man-hours of work later, this tribute to Ford at Le Mans in 1966 was created. Whatever the controversy, Ford had achieved what it set out to do and it would repeat its Le Mans winning ways for the next three years.

Images courtesy Ford of Europe / Motorsport Images / Automobilist