May 1st, May Day is a significant date on the calendar, an ancient festival of spring and a holiday in many European countries. Strung together, “mayday” is used internationally as a distress signal in the nautical and aviation worlds, a corruption of the French “m’aider” from the phrase “venez m’aider,” meaning “come and help me.”

In 1994, one could claim that May Day became a distress signal for the state of safety in motor racing, when Ayrton Senna lost his life on the seventh lap of the San Marino GP, at the Imola circuit in northern Italy.

For the greatest driver of his age to have been killed seemed impossible, ridiculous even and the shockwaves that followed would revolutionise the approach to racing safety. However, the way history has been rewritten suggests that, up until 1994, the governing body had taken a somewhat cavalier attitude to safety, which is definitely not the case. By then, the sport had moved on significantly from a time when it was commonplace for several F1 drivers to die in a season and prior to that terrible weekend in Italy, there had not been a fatality at a Grand Prix since Riccardo Paletti was killed in Canada in 1982, and Elio de Angelis died in a testing accident in 1986.

A move to take safety a step further began on the actual day of Senna’s death, when the F1 drivers decided to revive the dormant Grand Prix Drivers Association to give them a greater say in safety matters. This decision was prompted by the first tragedy of the Imola weekend, the death of Roland Ratzenberger in Saturday qualifying. It’s the way of the world that the death of a relatively unknown racer in only his third Grand Prix weekend, has been overshadowed by the passing of a three times world champion, but measures introduced after Ratzenberger’s death have definitely contributed to the safety of future generations of racers. In fact, the HANS device (Head and Neck Support) now mandatory in most forms of racing, was designed to prevent basal skull injuries of the type that killed the Austrian.

IMOLA 1994

The 1994 Imola weekend was a perfect storm of tragedy with a terrifying number of incidents that continued into the restarted race, even after Senna’s death. During Friday free practice, Rubens Barrichello suffered thankfully minor injuries when he had a horrific accident, rolling his Jordan several times. Then, at the first start on Sunday, Pedro Lamy in the Lotus was unsighted on the grid and did not see that JJ Lehto had stalled his Benetton and the ensuing collision sent debris flying into the crowd, leaving nine spectators with minor injuries. In the closing stages of the race, following a pit stop, a wheel came off the Minardi of Michele Alboreto, injuring four mechanics in the pit lane.

The Formula 1 circus couldn’t wait to leave the Imola track that night, unaware that the month of May had more shocks in store. A fortnight later in Monaco, Karl Wendlinger had a huge crash in the Sauber, exiting the tunnel during the first practice session. Thankfully, the Austrian recovered, but the incident effectively ended his F1 career. Just over a week later, Pedro Lamy had a massive crash in a Lotus, sustaining breaks to both legs, while testing at Silverstone.

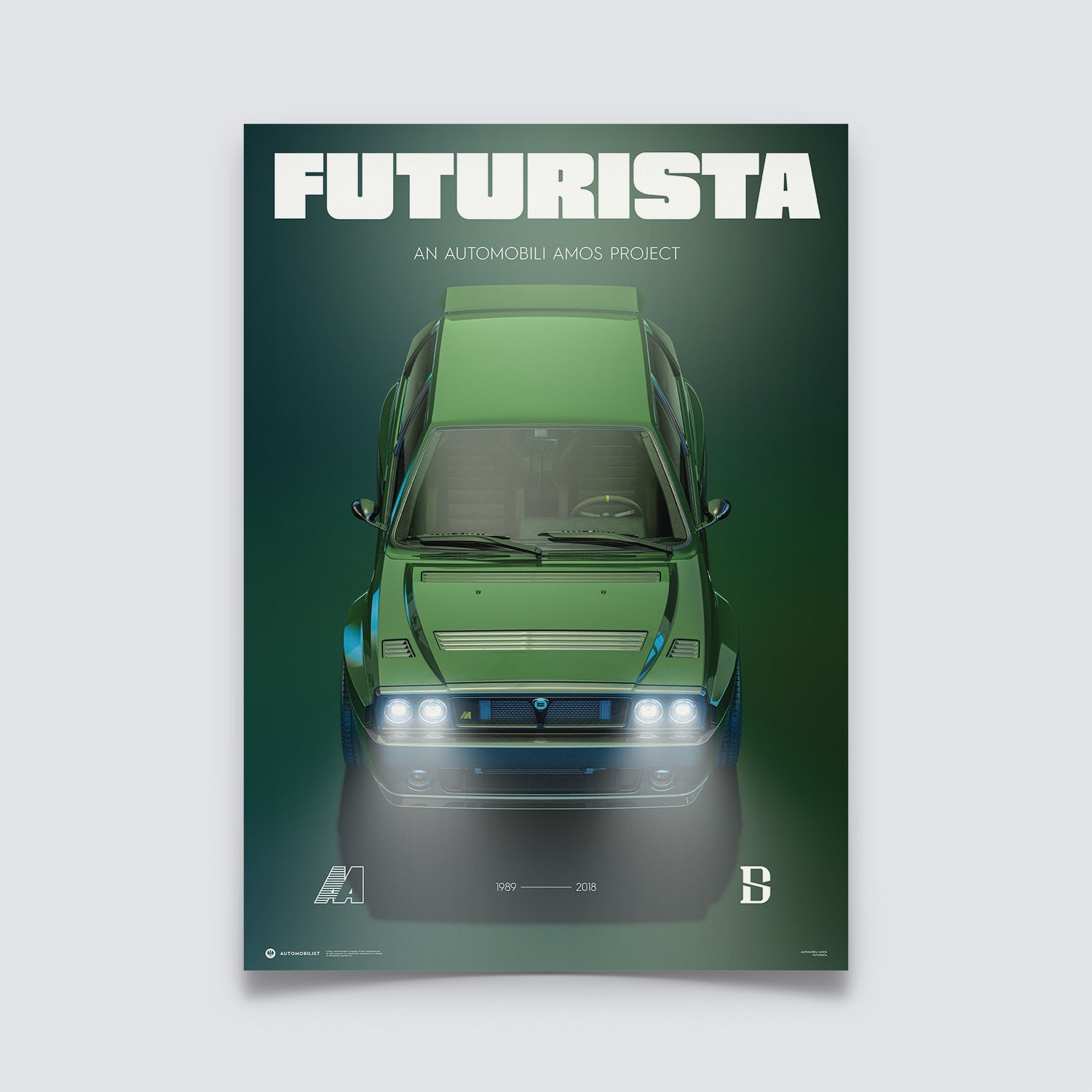

The month of May therefore had a profound effect on the way Formula 1 evolved and it was also the month that changed the face of the World Rally Championship. On 2nd May 1986, Henri Toivonen and his co-driver Sergio Cresto perished in an accident while leading the Tour of Corsica rally, in circumstances that are still something of a mystery. Their Group B Lancia failed to negotiate a left hand corner, plunged down a ravine and burst into flames. As had been the case at Imola, the rallying world couldn’t quite understand how the sport’s golden boy could have died in this way. The Group B cars were incredibly quick and spectacular and that era is regarded by many as the golden age of rallying. But within days of the tragedy, the FIA had banned these cars, whose light weight, advanced aerodynamics and massive horsepower (as much as 700 bhp) means that even over thirty years later, their performance has never been matched.

Motor sport will never be completely safe, but it’s a testament to the way the governing body and the industry has learned from past tragedies, that following Senna’s death, there had been no fatalities in Formula 1 for two decades until Jules Bianchi passed away in 2015, following his accident at the previous year’s Japanese Grand Prix. However, last year at the Belgian Grand Prix meeting, the young Frenchman Anthoine Hubert was killed in an accident during the Formula 2 race, proof that there is no room for complacency in the pursuit of safety.

Images credit: HOCH ZWEI / Juergen Tap / Roman Belogorodov / Shutterstock.com